Due to some dramatic elements, this period has been compared by many analysts to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

There are some similarities, including a scenario where a debt supercycle reaches its later stages.

However, there are also several key differences between now and then. Some better, some worse, but mainly just different.

Monday, March 30, 2020

Friday, March 27, 2020

40 years and 40 days

I Became a Disciplined Investor Over 40 Years. The Virus Broke Me in 40 Days.

I’ve survived — and even prospered through — four stock-market crashes. But nothing prepared me for this.

It’s Thursday morning, March 19 — four weeks into the coronavirus crash of 2020. The Dow Jones industrial average has opened down another 700 points, after plunging below 20,000 a day before. It’s down 30 percent in a month, the steepest drop ever, even worse than during the Great Depression.

The fall has been nauseating. Yet I know this is a time to be buying stocks based on rules I’ve developed over decades of investing. But in order to do that, I have to log on to my brokerage account. When I do, the first number I’ll see is the current market value of my portfolio.

Isolated at a farmhouse in rural New York, surrounded by wilderness, I haven’t looked in days. I don’t want to look now.

I decide I’d better check the weather forecast instead. And then there’s email to catch up on. An hour later, I’ve done nothing.

I’m paralyzed.

I’ve owned stocks for nearly 40 years. I’ve lived through, survived and even prospered through four crashes.

So I should be prepared. Yet, looking back at the last few weeks, I recognize that I’ve violated most of my time-tested rules. Whipsawed between optimism and despair as the bad news mounted and my daily life was upended, I’ve let emotions influence my decisions. I’m doing it again this morning.

I first bought a stock mutual fund during the summer of 1982, as soon as I’d saved enough money to invest. My father, a Cadillac-driving sales manager for NBC’s local TV and radio affiliates, had been an avid believer in the stock market, and he’d drummed his faith into me.

It turned out that 1982 was a great year to buy, not that I realized it at the time. For years, I enjoyed the positive reinforcement of a steadily rising market. I loved looking up my mutual fund in the newspaper stock tables. Over the next five years the market tripled.

On Oct. 19, 1987, I was visiting my brother, who was spending a semester in France. When I left my hotel in Strasbourg early the next morning, I noticed the front pages on newsstands carried banner headlines reporting the Dow had dropped “23.” I wondered why the American market was front-page news in France. I looked more closely and saw the 23 preceded a percentage symbol. The Dow had dropped an unfathomable 508 points in one day. On a percentage basis, it was the stock market’s worst day ever.

I felt a powerful urge to salvage what was left of my modest savings by selling. But I was far away and had no choice but to hold.

Once I was back in the United States, the market seemed to stabilize. But volatility soon returned. In one of those downdrafts, I panicked and sold my entire fund.

By September 1989, the market had recovered all its losses. I watched from the sidelines, waiting in vain for a good time to get back in.

I vowed to never again trade in a panic. I made a rule — never sell on a down day — and a corollary: Never buy on an up day.

That served me well over the next decade’s record bull market, fueled by the tech boom. Times were even headier than during the 1980s. I often overheard personal trainers at the gym boasting about their favorite tech stocks.

The notion of diversification was largely unknown to me. In early 2000, when the tech bubble burst and the next crash came, I was fully invested and stayed that way. I watched as the value of my investments shriveled. I stopped looking at stock tables, which at least provided some psychological comfort. I dropped my monthly paper statements into the trash unopened.

But at least I adhered to my 1987 principle: I did not sell.

In the wake of the two-year bear market, I refined my strategy. I figured that if I bought every time the market average declined by 10 percent from its previous high — the standard definition of a correction — and then bought some more after each subsequent decline of 10 percent, then I’d never be buying at the top of the cycle.

I didn’t think of this as market timing, since I made no prediction where the market was headed. My strategy was a variation of the now-widespread practice of portfolio rebalancing — selling some asset classes and buying others to maintain a steady allocation.

I put this system into practice during the 2008 financial crisis. I recall shocked reactions that October when — with the market plunging and others boasting that they’d had the foresight to get out — I said I was buying.

My timing was hardly perfect. The market fell by 10 percent on five occasions — so I had plenty of opportunities to add to my stock positions. The last came in March 2009. In hindsight, the first of those 10 percent declines was a foolish time to have been buying, given that the market went down another 40 percent. But I reaped the gains even on those early purchases during the record-setting bull market that ended this month. Back in 2009, I didn’t have to worry about getting back into the market. I was already there.

What’s another virus scare?

There have been only five 10 percent corrections since then, and each was a buying opportunity for me. None was followed by a second 10 percent decline. The last of these corrections came at the end of 2018. As cash built up in my account, I wondered when, if ever, I’d get another such opportunity. I grew impatient. On Feb. 19, the S&P 500 closed at a record high. No one seemed to see a bear market or recession on the horizon, even as stock multiples teetered at record highs and a strange virus began to spread.

Until a week later.

Stocks fell, slowly at first, then gaining steam. By Feb. 25 the S&P 500 had dropped 7.6 percent from its peak.

From a financial standpoint, I wasn’t worried about the virus. Infections were leveling off in China. There were a few cases in the United States, most in a single nursing home in Washington State. Everyone was saying we had better medical care, better air quality and more effective means to prevent its spread than China. As an investor, I’d lived through many virus scares — SARS, MERS, swine flu, Ebola — and their ravages had no discernible impact on American stocks. Even the devastating AIDS epidemic had little effect on the broader economy or booming market.

So I bought stock (a broad-based index fund) on Feb. 25, jumping the gun on my own 10 percent buying target. My pent-up eagerness and optimism overwhelmed my disciplined strategy. I didn’t make a conscious decision to violate it. I didn’t even think about it in my haste to take advantage of what I assumed would be a fleeting opportunity.

Stocks dropped a little more the next day. Then, on Feb. 27, the S&P plunged nearly 5 percent. Now the market was officially in a correction, its fastest ever, down 12 percent from the peak the prior week. The coronavirus had spread globally, including to the United States.

I realized I should have waited. I felt foolish and guilty for violating my rules. I vowed not to do it again.

The biggest drop since Black Monday

But how smart I felt the next Monday. The S&P soared nearly 5 percent, amid rumors the Federal Reserve was about to cut interest rates.

The high was short-lived. By the end of the week, the S&P had erased Monday’s gains. By now I was worried, too, but I’m not an infectious disease expert. I figured stocks had priced in the risks. What I did know was that they were now deep into a correction, and so I bought more.

My buying may have been premature the first time, but now I was back on track, sticking to my playbook. At a time of soaring uncertainty on so many fronts, I felt like I was taking charge of my destiny.

That was the last time that buying stocks felt good, like I was pouncing on a fleeting opportunity. It soon became a source of profound anxiety.

Over the first weekend in March, headlines were all about the explosive spread of the virus in Italy. Photos of deserted piazzas drove home the gravity of the situation. What had seemed a distant threat now seemed close to home.

If that weren’t bad enough, Russia and Saudi Arabia decided to launch an oil price war just as demand was collapsing. Oil prices plummeted, dragging down the entire energy sector.

I expected it would be a bad Monday in the markets, but it was even worse. Circuit breakers kicked in to halt chaotic trading. The S&P closed down that day by 7 percent, the biggest drop since Black Monday in 1987.

I summoned the nerve to look at my brokerage account. I was shocked: The stock portion was down far more than the broad U.S. market averages. My international stock index fund was down 20 percent from its February peak, and the emerging markets fund had lost a quarter of its value.

I thought back to my experience 33 years earlier, when I’d panicked at the headlines in Strasbourg. I tried to remind myself that short-term volatility aside, the long-term trajectory of the market has always been up. When the market goes down, it’s time to think about buying more stocks — a time that came much sooner than I’d hoped or expected.

On Thursday, March 12, after President Trump banned most air travel between the United States and continental Europe, and after economies around the world started shutting down, the carnage in the stock market was even worse than Monday. The S&P dropped 10 percent, leaving it 27 percent below its peak a few weeks earlier.

According to my own rules, it was time to buy.

I hardly noticed. I was busy canceling a planned vacation the next week to the Virgin Islands. I began pondering the prospect of my own isolation, something that even a few days earlier had seemed unthinkable.

Worse, a friend in Spain, a healthy 40-year-old I had just visited in November, had fallen seriously ill with the virus. He was in a coma in a Madrid hospital.

I was worried about the spread of the disease. I wasn’t thinking about the stock market or my rapidly declining net worth.

Record-setting volatility

My strategy for trading isn’t meant to be rigid, only to be rational. It doesn’t matter if I miss a percentage point or two here or there, or if my timing is a little off, or if more important matters take precedence — as they have now. Two more friends told me they have the virus. Still, during the following days, when I pondered the rush of events during some long walks along a country road, I recognized I was running out of excuses for inaction. I knew I should be buying again, with the S&P remaining well below my 20 percent target. But trading was more volatile than anything I’d ever witnessed. The S&P logged a record seven straight days of swings of 4 percent or more.

That Friday, March 13, stock markets staged a late-afternoon rally as Mr. Trump promised new measures to contain the virus and shore up the economy. The S&P 500 closed almost exactly 20 percent below its peak. Still I did nothing.

It was just as well. On Monday, the market collapsed, erasing all of Friday’s gains. The Dow fell below the 20,000 milestone for the first time in three years. Markets were now down 30 percent. It was time for me to buy.

Having skipped the 20 percent buying “opportunity,” I knew it was time to step up. But I wasn’t going to do it on a day the markets had been in free fall. And in any event, I was back to avoiding my brokerage’s website.

The next day the stock market jumped higher. I felt a strong temptation to buy, gripped by the notion that the worst might be over. I worried I was missing the bottom by again failing to act on my strategy. But the 30 percent window had closed, and I reminded myself that my rule is never to buy on an up day.

The next day brought what seemed like good news: New infections in China had dropped to zero. Even so, that morning markets sank, again triggering my 30 percent buying target. This time I was determined to act.

And yet I dawdled. I checked the news, the weather, my emails. I told myself this was absurd. Whether I looked or not, my portfolio value was what it was.

So I looked. It was bad, but not nearly the shock of the last time (perhaps because percentage declines now translated to lower dollar amounts). I still had ample cash on hand as interest and dividends had accumulated over recent years.

So I stepped in and bought.

I won’t say I felt euphoric, but I felt better than I had in weeks, at least about my personal finances. I’d mustered the courage to face the truth, however grim. I’d acted according to a plan. I had more cash if needed for the next 10 percent decline.

My renewed confidence survived the next downdraft, which came the very next day.

‘Ashamed, foolish, like you screwed up’

This week I described my recent investing struggles to Frank Murtha, a managing partner of the consulting firm MarketPysch and an expert in behavioral finance. He said nothing I told him was unusual, even among seasoned investors.

My reluctance to look at my portfolio was common, he said. “Watching yourself have less money is painful,” he said. “It’s not just that you’re poorer. You also feel ashamed, foolish, like you screwed up. One of the toughest things is to separate your money from your ego and identity.”

He gave me credit for gathering the courage to face reality and then to buy. “Nothing relieves anxiety more than taking action,” he said. “You can take small actions that address the emotional need to do something without putting your finances at undue risk.”

Stocks are one of the few assets that psychologically become harder to buy as they become cheaper. “Every decision to buy is met with negative reinforcement,” Mr. Murtha said. Even he missed the great buying opportunity in March 2009. “I was too scared,” he said.

At least I didn’t commit what Mr. Murtha considers the most serious error, which is to sell into a steep decline. “That’s where people really get hurt,” he said. “Once you’re out, the emotional leverage works against you. Either the market drops further, which confirms your fear. Or it goes up, and you don’t want to buy after you just sold. Then it gets further and further away from you. People don’t realize how hard it is to get back in.”

The market soared. I felt no elation.

Nothing I experienced in the past prepared me for the speed of this market crash. The decline after stocks peaked in March 2000 lasted until October 2002 — two and a half years. The most recent bear market, which started in 2007, lasted 17 months. Nobody knows how long this bear market will last.

I take heart from this: During that previous bear market, the S&P was never down more than 50 percent from its 2007 peak. Even in the Great Depression, the worst bear market ever, the S&P dropped 86 percent. Small comfort, perhaps, but it never went to zero. And after those steep drops, the market not only recovered, but eventually went on to record highs.

This week brought some good news. My friend in Spain emerged from his coma. Doctors say his recovery will be slow, but they’re optimistic.

On Tuesday the market soared, followed by two more days of gains. This time I felt no elation. Some of the biggest rallies have come in the middle of the worst bear markets.

My next target is when the S&P falls 40 percent from its peak. I may be buying again soon.

-- by James B. Stewart, New York Times, 3/27/20

I’ve survived — and even prospered through — four stock-market crashes. But nothing prepared me for this.

It’s Thursday morning, March 19 — four weeks into the coronavirus crash of 2020. The Dow Jones industrial average has opened down another 700 points, after plunging below 20,000 a day before. It’s down 30 percent in a month, the steepest drop ever, even worse than during the Great Depression.

The fall has been nauseating. Yet I know this is a time to be buying stocks based on rules I’ve developed over decades of investing. But in order to do that, I have to log on to my brokerage account. When I do, the first number I’ll see is the current market value of my portfolio.

Isolated at a farmhouse in rural New York, surrounded by wilderness, I haven’t looked in days. I don’t want to look now.

I decide I’d better check the weather forecast instead. And then there’s email to catch up on. An hour later, I’ve done nothing.

I’m paralyzed.

I’ve owned stocks for nearly 40 years. I’ve lived through, survived and even prospered through four crashes.

So I should be prepared. Yet, looking back at the last few weeks, I recognize that I’ve violated most of my time-tested rules. Whipsawed between optimism and despair as the bad news mounted and my daily life was upended, I’ve let emotions influence my decisions. I’m doing it again this morning.

I first bought a stock mutual fund during the summer of 1982, as soon as I’d saved enough money to invest. My father, a Cadillac-driving sales manager for NBC’s local TV and radio affiliates, had been an avid believer in the stock market, and he’d drummed his faith into me.

It turned out that 1982 was a great year to buy, not that I realized it at the time. For years, I enjoyed the positive reinforcement of a steadily rising market. I loved looking up my mutual fund in the newspaper stock tables. Over the next five years the market tripled.

On Oct. 19, 1987, I was visiting my brother, who was spending a semester in France. When I left my hotel in Strasbourg early the next morning, I noticed the front pages on newsstands carried banner headlines reporting the Dow had dropped “23.” I wondered why the American market was front-page news in France. I looked more closely and saw the 23 preceded a percentage symbol. The Dow had dropped an unfathomable 508 points in one day. On a percentage basis, it was the stock market’s worst day ever.

I felt a powerful urge to salvage what was left of my modest savings by selling. But I was far away and had no choice but to hold.

Once I was back in the United States, the market seemed to stabilize. But volatility soon returned. In one of those downdrafts, I panicked and sold my entire fund.

By September 1989, the market had recovered all its losses. I watched from the sidelines, waiting in vain for a good time to get back in.

I vowed to never again trade in a panic. I made a rule — never sell on a down day — and a corollary: Never buy on an up day.

That served me well over the next decade’s record bull market, fueled by the tech boom. Times were even headier than during the 1980s. I often overheard personal trainers at the gym boasting about their favorite tech stocks.

The notion of diversification was largely unknown to me. In early 2000, when the tech bubble burst and the next crash came, I was fully invested and stayed that way. I watched as the value of my investments shriveled. I stopped looking at stock tables, which at least provided some psychological comfort. I dropped my monthly paper statements into the trash unopened.

But at least I adhered to my 1987 principle: I did not sell.

In the wake of the two-year bear market, I refined my strategy. I figured that if I bought every time the market average declined by 10 percent from its previous high — the standard definition of a correction — and then bought some more after each subsequent decline of 10 percent, then I’d never be buying at the top of the cycle.

I didn’t think of this as market timing, since I made no prediction where the market was headed. My strategy was a variation of the now-widespread practice of portfolio rebalancing — selling some asset classes and buying others to maintain a steady allocation.

I put this system into practice during the 2008 financial crisis. I recall shocked reactions that October when — with the market plunging and others boasting that they’d had the foresight to get out — I said I was buying.

My timing was hardly perfect. The market fell by 10 percent on five occasions — so I had plenty of opportunities to add to my stock positions. The last came in March 2009. In hindsight, the first of those 10 percent declines was a foolish time to have been buying, given that the market went down another 40 percent. But I reaped the gains even on those early purchases during the record-setting bull market that ended this month. Back in 2009, I didn’t have to worry about getting back into the market. I was already there.

What’s another virus scare?

There have been only five 10 percent corrections since then, and each was a buying opportunity for me. None was followed by a second 10 percent decline. The last of these corrections came at the end of 2018. As cash built up in my account, I wondered when, if ever, I’d get another such opportunity. I grew impatient. On Feb. 19, the S&P 500 closed at a record high. No one seemed to see a bear market or recession on the horizon, even as stock multiples teetered at record highs and a strange virus began to spread.

Until a week later.

Stocks fell, slowly at first, then gaining steam. By Feb. 25 the S&P 500 had dropped 7.6 percent from its peak.

From a financial standpoint, I wasn’t worried about the virus. Infections were leveling off in China. There were a few cases in the United States, most in a single nursing home in Washington State. Everyone was saying we had better medical care, better air quality and more effective means to prevent its spread than China. As an investor, I’d lived through many virus scares — SARS, MERS, swine flu, Ebola — and their ravages had no discernible impact on American stocks. Even the devastating AIDS epidemic had little effect on the broader economy or booming market.

So I bought stock (a broad-based index fund) on Feb. 25, jumping the gun on my own 10 percent buying target. My pent-up eagerness and optimism overwhelmed my disciplined strategy. I didn’t make a conscious decision to violate it. I didn’t even think about it in my haste to take advantage of what I assumed would be a fleeting opportunity.

Stocks dropped a little more the next day. Then, on Feb. 27, the S&P plunged nearly 5 percent. Now the market was officially in a correction, its fastest ever, down 12 percent from the peak the prior week. The coronavirus had spread globally, including to the United States.

I realized I should have waited. I felt foolish and guilty for violating my rules. I vowed not to do it again.

The biggest drop since Black Monday

But how smart I felt the next Monday. The S&P soared nearly 5 percent, amid rumors the Federal Reserve was about to cut interest rates.

The high was short-lived. By the end of the week, the S&P had erased Monday’s gains. By now I was worried, too, but I’m not an infectious disease expert. I figured stocks had priced in the risks. What I did know was that they were now deep into a correction, and so I bought more.

My buying may have been premature the first time, but now I was back on track, sticking to my playbook. At a time of soaring uncertainty on so many fronts, I felt like I was taking charge of my destiny.

That was the last time that buying stocks felt good, like I was pouncing on a fleeting opportunity. It soon became a source of profound anxiety.

Over the first weekend in March, headlines were all about the explosive spread of the virus in Italy. Photos of deserted piazzas drove home the gravity of the situation. What had seemed a distant threat now seemed close to home.

If that weren’t bad enough, Russia and Saudi Arabia decided to launch an oil price war just as demand was collapsing. Oil prices plummeted, dragging down the entire energy sector.

I expected it would be a bad Monday in the markets, but it was even worse. Circuit breakers kicked in to halt chaotic trading. The S&P closed down that day by 7 percent, the biggest drop since Black Monday in 1987.

I summoned the nerve to look at my brokerage account. I was shocked: The stock portion was down far more than the broad U.S. market averages. My international stock index fund was down 20 percent from its February peak, and the emerging markets fund had lost a quarter of its value.

I thought back to my experience 33 years earlier, when I’d panicked at the headlines in Strasbourg. I tried to remind myself that short-term volatility aside, the long-term trajectory of the market has always been up. When the market goes down, it’s time to think about buying more stocks — a time that came much sooner than I’d hoped or expected.

On Thursday, March 12, after President Trump banned most air travel between the United States and continental Europe, and after economies around the world started shutting down, the carnage in the stock market was even worse than Monday. The S&P dropped 10 percent, leaving it 27 percent below its peak a few weeks earlier.

According to my own rules, it was time to buy.

I hardly noticed. I was busy canceling a planned vacation the next week to the Virgin Islands. I began pondering the prospect of my own isolation, something that even a few days earlier had seemed unthinkable.

Worse, a friend in Spain, a healthy 40-year-old I had just visited in November, had fallen seriously ill with the virus. He was in a coma in a Madrid hospital.

I was worried about the spread of the disease. I wasn’t thinking about the stock market or my rapidly declining net worth.

Record-setting volatility

My strategy for trading isn’t meant to be rigid, only to be rational. It doesn’t matter if I miss a percentage point or two here or there, or if my timing is a little off, or if more important matters take precedence — as they have now. Two more friends told me they have the virus. Still, during the following days, when I pondered the rush of events during some long walks along a country road, I recognized I was running out of excuses for inaction. I knew I should be buying again, with the S&P remaining well below my 20 percent target. But trading was more volatile than anything I’d ever witnessed. The S&P logged a record seven straight days of swings of 4 percent or more.

That Friday, March 13, stock markets staged a late-afternoon rally as Mr. Trump promised new measures to contain the virus and shore up the economy. The S&P 500 closed almost exactly 20 percent below its peak. Still I did nothing.

It was just as well. On Monday, the market collapsed, erasing all of Friday’s gains. The Dow fell below the 20,000 milestone for the first time in three years. Markets were now down 30 percent. It was time for me to buy.

Having skipped the 20 percent buying “opportunity,” I knew it was time to step up. But I wasn’t going to do it on a day the markets had been in free fall. And in any event, I was back to avoiding my brokerage’s website.

The next day the stock market jumped higher. I felt a strong temptation to buy, gripped by the notion that the worst might be over. I worried I was missing the bottom by again failing to act on my strategy. But the 30 percent window had closed, and I reminded myself that my rule is never to buy on an up day.

The next day brought what seemed like good news: New infections in China had dropped to zero. Even so, that morning markets sank, again triggering my 30 percent buying target. This time I was determined to act.

And yet I dawdled. I checked the news, the weather, my emails. I told myself this was absurd. Whether I looked or not, my portfolio value was what it was.

So I looked. It was bad, but not nearly the shock of the last time (perhaps because percentage declines now translated to lower dollar amounts). I still had ample cash on hand as interest and dividends had accumulated over recent years.

So I stepped in and bought.

I won’t say I felt euphoric, but I felt better than I had in weeks, at least about my personal finances. I’d mustered the courage to face the truth, however grim. I’d acted according to a plan. I had more cash if needed for the next 10 percent decline.

My renewed confidence survived the next downdraft, which came the very next day.

‘Ashamed, foolish, like you screwed up’

This week I described my recent investing struggles to Frank Murtha, a managing partner of the consulting firm MarketPysch and an expert in behavioral finance. He said nothing I told him was unusual, even among seasoned investors.

My reluctance to look at my portfolio was common, he said. “Watching yourself have less money is painful,” he said. “It’s not just that you’re poorer. You also feel ashamed, foolish, like you screwed up. One of the toughest things is to separate your money from your ego and identity.”

He gave me credit for gathering the courage to face reality and then to buy. “Nothing relieves anxiety more than taking action,” he said. “You can take small actions that address the emotional need to do something without putting your finances at undue risk.”

Stocks are one of the few assets that psychologically become harder to buy as they become cheaper. “Every decision to buy is met with negative reinforcement,” Mr. Murtha said. Even he missed the great buying opportunity in March 2009. “I was too scared,” he said.

At least I didn’t commit what Mr. Murtha considers the most serious error, which is to sell into a steep decline. “That’s where people really get hurt,” he said. “Once you’re out, the emotional leverage works against you. Either the market drops further, which confirms your fear. Or it goes up, and you don’t want to buy after you just sold. Then it gets further and further away from you. People don’t realize how hard it is to get back in.”

The market soared. I felt no elation.

Nothing I experienced in the past prepared me for the speed of this market crash. The decline after stocks peaked in March 2000 lasted until October 2002 — two and a half years. The most recent bear market, which started in 2007, lasted 17 months. Nobody knows how long this bear market will last.

I take heart from this: During that previous bear market, the S&P was never down more than 50 percent from its 2007 peak. Even in the Great Depression, the worst bear market ever, the S&P dropped 86 percent. Small comfort, perhaps, but it never went to zero. And after those steep drops, the market not only recovered, but eventually went on to record highs.

This week brought some good news. My friend in Spain emerged from his coma. Doctors say his recovery will be slow, but they’re optimistic.

On Tuesday the market soared, followed by two more days of gains. This time I felt no elation. Some of the biggest rallies have come in the middle of the worst bear markets.

My next target is when the S&P falls 40 percent from its peak. I may be buying again soon.

-- by James B. Stewart, New York Times, 3/27/20

Thursday, March 26, 2020

market panics in hindsight

Do you remember where you were on Oct. 27, 1997?

Probably not. I don’t either. But on that day, the Dow plunged 550 points, which was roughly the same amount in percentage terms (7%) as today’s 2,000-point drop. In the late 1990s, the Asian financial crisis was the reason for that panic. But like many panics, as time passes, they seem to be much less meaningful in the rear view mirror.

Of course, this isn’t true for all panics. We will never forget events such as the 9/11 tragedy, or Sept. 15, 2008, when Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, precipitating a swift run on the financial system and a severe economic contraction that the country hadn’t seen since the Great Depression. There was the Panic of 1893, which led to a depression that was arguably as severe as the Great Depression (and, in fact, was called just that until the Depression of the 1930s arrived). And, of course, there was the Great Depression itself.

But for each of these great panics, there are scores of smaller panics that seemed very significant at the time, but in hindsight look like nothing more than a blip on the radar.

The forgotten "panics"

Examples of such “mini-panics” that felt like full-blown panics at the time include the 1998 Russian debt crisis, where Moscow shocked the world by defaulting on their own ruble debt. The chaotic price movements in the markets crushed a hugely leveraged hedge fund called Long-Term Capital, which nearly drowned the banking system with its massive trading liabilities. The fund was bailed out by its own lenders (thanks to some strong-arming by the New York Fed) and this prevented the fund’s immediate liquidation, which stopped the panic.

Another panic occurred in 2011, where fears of a “double-dip” recession (remember that term?) coincided with political gridlock and a debt ceiling standoff that led to the first ever downgrade of the credit of the U.S. government. This seemed like a big deal at the time, and the market plunged roughly 17% from peak to trough, with many bank stocks and other cyclicals down 40% or more.

There was the Panic of 1907, where the failure of a major New York financial institution led to a city-wide run on the banking system, which drained liquidity from the economy and caused a sharp contraction as merchants couldn’t fund their inventory and corporations couldn’t make payroll. This crisis was historic because it eventually led to the creation of the Federal Reserve, but in fact the panic and subsequent downturn turned out to be very short-lived (I’ve written about this fascinating situation here and here).

And in the aforementioned 1997 panic, fast-growing Southeast Asian export nations (“Asian Tigers”) relied on foreign investment to finance their economic growth, but they went bust when rising U.S. interest rates made it harder to compete for foreign capital and a stronger dollar made exports less competitive for these dollar-pegged nations. The Tigers allowed money to freely flow into their countries in good times. But where money can easily enter, it can also quickly exit, and in 1997 an effective run-on-the-bank occurred in these nations, resulting in painful devaluations and economic collapses. This led to a major selloff across the world, and in fact was the last time (until today) that the U.S. stock market used its “circuit breaker” to shut down trading after markets plummeted.

There were even smaller scares such as the bond market debacle of 1994, the SARS outbreak in 2003, the “Flash Crash” in 2010 (also accompanied by the dreaded double-dip recession fear), the OPEC-fueled oil price rout (sound familiar?) that led to the worst start to the year in stock market history in 2016 and most recently, the trade war that caused a peak to trough drawdown of nearly 20% in the S&P 500 in the fourth quarter of 2018.

These mini-panics are only a small sample. There are countless examples that you can find when reading about the Go-Go years of the 1960s, the stagflation years of the 1970s and the junk bond years of the 1980s.

There are a number of lessons that can be learned by studying these past events, including the pattern of behavior that is so eerily similar in each of these panics, but there are two other takeaways I’ll mention here:

550 points used to be scary

Referencing Dow points is usually a useless exercise, but I use it to show how far the market has come from the days when a 550-point decline was a panic that required a temporary closure of the market.

My point is the stock market rewards investors who are long-term-oriented and patient. Investing isn’t easy, but it is simple. Owning a stake in a broad swath of American companies and ignoring the inevitable ups and downs is a surefire way to achieve success over time.

A quarter century from now, a 2000 point decline will likely be a much more normal 1% to 2% drop, just like a 550-point drop is today.

Stocks appreciate over time, and long-term investors get rewarded.

Time heals all wounds

Three years from now, we’ll all be looking back at this time as a great buying opportunity. It’s an extreme likelihood. I don’t know if this panic is going to get worse, and I never know in real time whether the panic is going to be the once-in-a-generation kind, but I do know that it is extremely unlikely. Nearly all panics wind up being “mini-panics” in hindsight, and they also turn out to be fabulous buying opportunities.

They are also viewed with relative indifference after a few years pass. Many people allow their memories of the fear to fade as time passes. Events that seemed important then are relatively meaningless now when filtered through the prism of time.

But they all seemed scary at the time.

And they were all great opportunities to buy stocks.

The time arbitrage loophole

I don’t know if this current coronavirus panic accelerates before it subsides, but I do know it will subside. And at some point, when enough time passes (often not much time is required), we’ll all agree that this was a great time to buy stocks.

What creates opportunity in markets is that in the current moment, we don’t all agree. Some view this as a buying opportunity, others think it’s a great time to sell stocks, or that it’s prudent to wait for “more clarity.” This disparity of interpretation is why stocks get mispriced. I’ve talked often about how Saber’s investment approach relies on time horizon edge, and this is a perfect example of why this approach can be successful over time. Stocks of great companies are getting sold because the earnings outlook looks bad this year, even when there is little debate about the long-term prospects for the business.

Some investors are in fact panic selling out of fear, others are more rationally selling because they don’t want to own a business that will have a bad year. And this creates opportunities for those who want to buy a stake in companies as a long-term part-owner.

Steve Jobs used to tell people to go for a walk and “zoom out”, to change your perspective and to look at the big picture. Sometimes it helps to zoom out and detach yourself from the current situation.

I don’t know what happens tomorrow or next week, or next month, or next year. But I am confident that we’ll look back in a few years and identify this as one of those times where it was great to be a buyer of stocks.

-- John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber is the general partner and manager of an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships. Saber’s strategy is to make very carefully selected investments in undervalued stocks of great businesses.

Probably not. I don’t either. But on that day, the Dow plunged 550 points, which was roughly the same amount in percentage terms (7%) as today’s 2,000-point drop. In the late 1990s, the Asian financial crisis was the reason for that panic. But like many panics, as time passes, they seem to be much less meaningful in the rear view mirror.

Of course, this isn’t true for all panics. We will never forget events such as the 9/11 tragedy, or Sept. 15, 2008, when Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, precipitating a swift run on the financial system and a severe economic contraction that the country hadn’t seen since the Great Depression. There was the Panic of 1893, which led to a depression that was arguably as severe as the Great Depression (and, in fact, was called just that until the Depression of the 1930s arrived). And, of course, there was the Great Depression itself.

But for each of these great panics, there are scores of smaller panics that seemed very significant at the time, but in hindsight look like nothing more than a blip on the radar.

The forgotten "panics"

Examples of such “mini-panics” that felt like full-blown panics at the time include the 1998 Russian debt crisis, where Moscow shocked the world by defaulting on their own ruble debt. The chaotic price movements in the markets crushed a hugely leveraged hedge fund called Long-Term Capital, which nearly drowned the banking system with its massive trading liabilities. The fund was bailed out by its own lenders (thanks to some strong-arming by the New York Fed) and this prevented the fund’s immediate liquidation, which stopped the panic.

Another panic occurred in 2011, where fears of a “double-dip” recession (remember that term?) coincided with political gridlock and a debt ceiling standoff that led to the first ever downgrade of the credit of the U.S. government. This seemed like a big deal at the time, and the market plunged roughly 17% from peak to trough, with many bank stocks and other cyclicals down 40% or more.

There was the Panic of 1907, where the failure of a major New York financial institution led to a city-wide run on the banking system, which drained liquidity from the economy and caused a sharp contraction as merchants couldn’t fund their inventory and corporations couldn’t make payroll. This crisis was historic because it eventually led to the creation of the Federal Reserve, but in fact the panic and subsequent downturn turned out to be very short-lived (I’ve written about this fascinating situation here and here).

And in the aforementioned 1997 panic, fast-growing Southeast Asian export nations (“Asian Tigers”) relied on foreign investment to finance their economic growth, but they went bust when rising U.S. interest rates made it harder to compete for foreign capital and a stronger dollar made exports less competitive for these dollar-pegged nations. The Tigers allowed money to freely flow into their countries in good times. But where money can easily enter, it can also quickly exit, and in 1997 an effective run-on-the-bank occurred in these nations, resulting in painful devaluations and economic collapses. This led to a major selloff across the world, and in fact was the last time (until today) that the U.S. stock market used its “circuit breaker” to shut down trading after markets plummeted.

There were even smaller scares such as the bond market debacle of 1994, the SARS outbreak in 2003, the “Flash Crash” in 2010 (also accompanied by the dreaded double-dip recession fear), the OPEC-fueled oil price rout (sound familiar?) that led to the worst start to the year in stock market history in 2016 and most recently, the trade war that caused a peak to trough drawdown of nearly 20% in the S&P 500 in the fourth quarter of 2018.

These mini-panics are only a small sample. There are countless examples that you can find when reading about the Go-Go years of the 1960s, the stagflation years of the 1970s and the junk bond years of the 1980s.

There are a number of lessons that can be learned by studying these past events, including the pattern of behavior that is so eerily similar in each of these panics, but there are two other takeaways I’ll mention here:

- Notice the number of Dow points that a 7% drop was in 1997.

- Notice how little you care about (or even remember) the vast majority of these mini-panics.

550 points used to be scary

Referencing Dow points is usually a useless exercise, but I use it to show how far the market has come from the days when a 550-point decline was a panic that required a temporary closure of the market.

My point is the stock market rewards investors who are long-term-oriented and patient. Investing isn’t easy, but it is simple. Owning a stake in a broad swath of American companies and ignoring the inevitable ups and downs is a surefire way to achieve success over time.

A quarter century from now, a 2000 point decline will likely be a much more normal 1% to 2% drop, just like a 550-point drop is today.

Stocks appreciate over time, and long-term investors get rewarded.

Time heals all wounds

Three years from now, we’ll all be looking back at this time as a great buying opportunity. It’s an extreme likelihood. I don’t know if this panic is going to get worse, and I never know in real time whether the panic is going to be the once-in-a-generation kind, but I do know that it is extremely unlikely. Nearly all panics wind up being “mini-panics” in hindsight, and they also turn out to be fabulous buying opportunities.

They are also viewed with relative indifference after a few years pass. Many people allow their memories of the fear to fade as time passes. Events that seemed important then are relatively meaningless now when filtered through the prism of time.

But they all seemed scary at the time.

And they were all great opportunities to buy stocks.

The time arbitrage loophole

I don’t know if this current coronavirus panic accelerates before it subsides, but I do know it will subside. And at some point, when enough time passes (often not much time is required), we’ll all agree that this was a great time to buy stocks.

What creates opportunity in markets is that in the current moment, we don’t all agree. Some view this as a buying opportunity, others think it’s a great time to sell stocks, or that it’s prudent to wait for “more clarity.” This disparity of interpretation is why stocks get mispriced. I’ve talked often about how Saber’s investment approach relies on time horizon edge, and this is a perfect example of why this approach can be successful over time. Stocks of great companies are getting sold because the earnings outlook looks bad this year, even when there is little debate about the long-term prospects for the business.

Some investors are in fact panic selling out of fear, others are more rationally selling because they don’t want to own a business that will have a bad year. And this creates opportunities for those who want to buy a stake in companies as a long-term part-owner.

Steve Jobs used to tell people to go for a walk and “zoom out”, to change your perspective and to look at the big picture. Sometimes it helps to zoom out and detach yourself from the current situation.

I don’t know what happens tomorrow or next week, or next month, or next year. But I am confident that we’ll look back in a few years and identify this as one of those times where it was great to be a buyer of stocks.

-- John Huber is the founder of Saber Capital Management, LLC. Saber is the general partner and manager of an investment fund modeled after the original Buffett partnerships. Saber’s strategy is to make very carefully selected investments in undervalued stocks of great businesses.

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

a technical look at this bear market

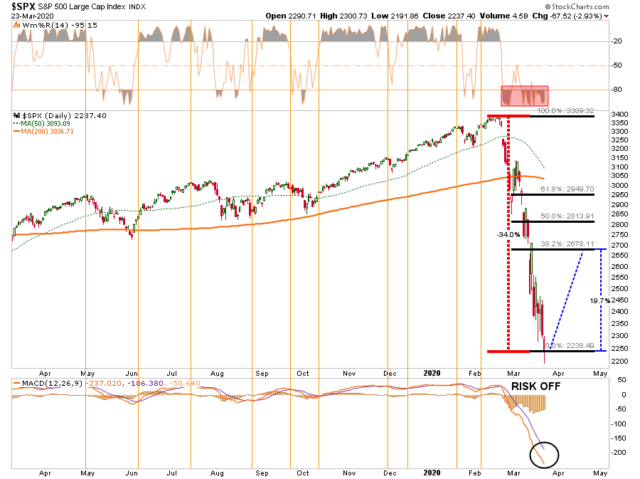

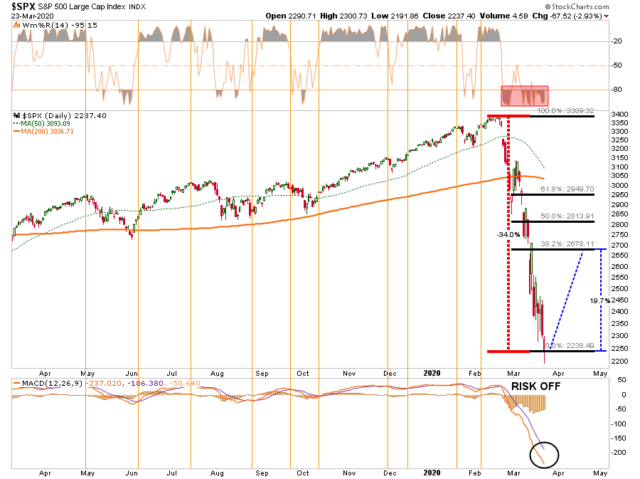

The current bear market is exhibiting many of the same "technical traits" as seen in both the "Dot.com" and "Financial Crisis."

In each previous case, the market experienced a parabolic advance to the initial peak. A correction ensued, which was dismissed by the mainstream media, and investors alike, as just a "pause that refreshes." They were seemingly proved correct as the markets rebounded shortly thereafter and even set all-time highs. Investors, complacent in the belief that "this time was different" (1999 - a new paradigm, 2007 - Goldilocks economy), continued to hold out hopes the bull market was set to continue.

That was a mistake.

Also, in each period, once the monthly "sell signal" was triggered from a high level, the ensuing correction process took months to complete. This not only reset the market, but valuations as well. In both previous periods, reflexive rallies occurred, which eventually failed. While the 2008 plunge following the Lehman crisis was most similar to the current environment, there was a brief rally following the passage of TARP, which sucked investors in before the additional 22% decline in the first two months of 2009.

Most importantly, the market got very oversold early in both previous bear markets, and stayed that way for the entirety of the bear market. Currently, the market has only just now gotten to a similar oversold condition.

What all the indicators currently suggest is that, while the current correction has been swift and brutal, bear markets are not resolved in a single month.

This is going to take some time.

Bear Market Rally

Over the past couple of weeks, we have been talking about a potential reflexive bounce.

From a purely technical basis, the extreme downside extension, and potential selling exhaustion, has set the markets up for a fairly strong reflexive bounce. This is where fun with math comes in.

As shown in the chart below, after a 35% decline in the markets from the previous highs, a rally to the 38.2% Fibonacci retracement would encompass a 20% advance. Such an advance will "lure" investors back into the market, thinking the "bear market" is over.

This is what "bear market rallies" do and generally inflict the most pain possible on unwitting investors. The reasons for this are many, but primarily investors who were trapped in the recent decline will use the rally to "flee" the markets permanently.

More importantly, as noted above, "bear markets" are not resolved in a single month. Currently, there are too many investors trying to figure out where "the bottom" is, so they can "buy" it.

Bear markets do not end in optimism; they end in despair.

Looking back at 2008, numerous indicators suggest the "bear market" has only just begun. While this does NOT rule out a fairly strong reflexive rally, it suggests that any rally will ultimately fail as the bear market completes its cycle.

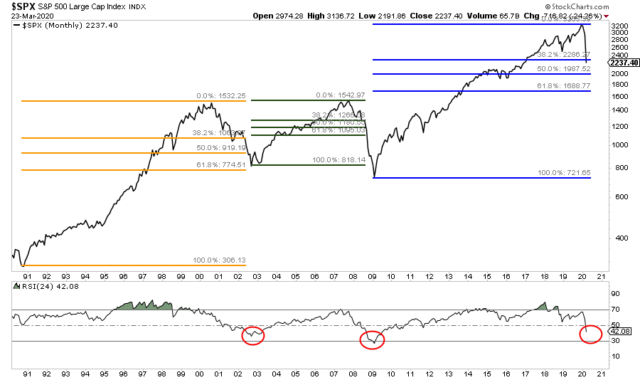

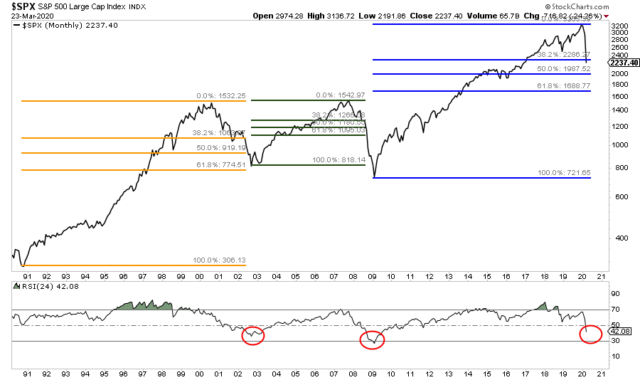

This can be seen more clearly in the monthly chart below, which looks at both previous bull and bear markets using a Fibonacci retracement. As shown, from the peak of both previous bull market "bubbles," the market reversed 61.8% of the advance during the "Dot.com" crash, and more than 100% of the advance during the "Financial Crisis."

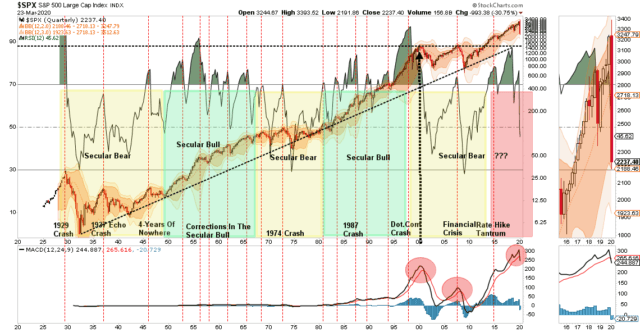

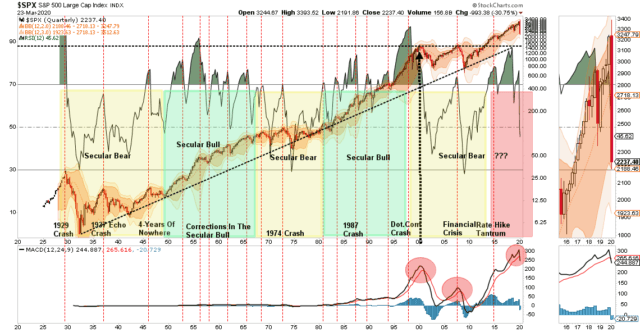

Given the current bull market cycle was longer, more levered, and more extended than both previous bull markets, a 38.2% decline is unlikely to fulfill the requirements of this reversion. Our ultimate target of 1600-1800 on the S&P 500 remains confirmed by the quarterly chart below.

The current correction process has only just triggered a quarterly sell signal combined with a break from an extreme deviation of the long-term bull-trend back to the 1930s. Both previous bull market peaks coincide with the long-term bull trend at about 1600 on the S&P currently. Given all the stimulus being infused into the markets currently, we broaden our bear market bottom target to 1600-1800, as noted.

The technical signals, which do indeed lag short-term turns in the market, all confirm the "bear market" is only just awakening. While bullish reflexive rallies are very likely, and should be used to your advantage, this is a "traders" market for the time being.

In other words, the new mantra for the market, for the time being, will be to "Sell Rallies" rather than "Buy The Dip."

Yes, the market will rally, and likely substantially so. Just don't forget to take action, make changes, and get on the right side of the trade, before the "bear returns."

Let me conclude by reminding you of Bob Farrell's Rule #8 from our recent newsletter:

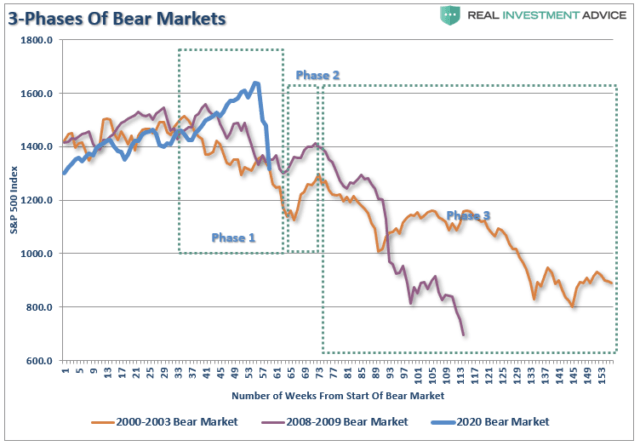

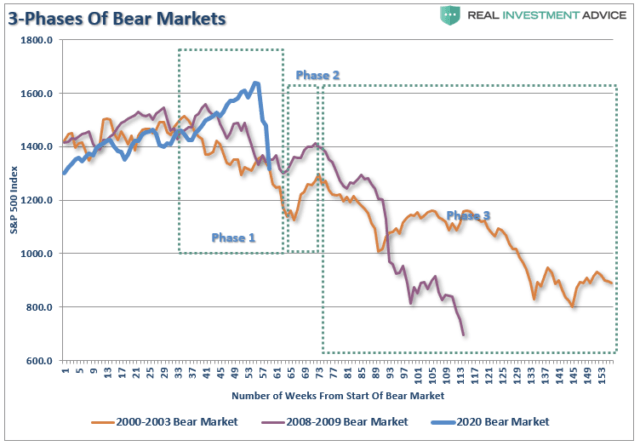

Bear markets have three stages - sharp down, reflexive rebound and a drawn-out fundamental downtrend

Bear markets often START with a sharp and swift decline.

After this decline, there is an oversold bounce that retraces a portion of that decline.

The longer-term decline then continues, at a slower and more grinding pace, as the fundamentals deteriorate.

Dow Theory also suggests that bear markets consist of three down legs with reflexive rebounds in between.

The chart above shows the stages of the last two primary cyclical bear markets versus today (the 2020 scale has been adjusted to match.)

As would be expected, the "Phase 1" selloff has been brutal.

That selloff sets up a "reflexive bounce." For many individuals, they will "feel like" they are "safe." This is how "bear market rallies" lure investors back in just before they are mauled again in "Phase 3."

Just like in 2000, and 2008, the media/Wall Street will be telling you to just "hold on." Unfortunately, by the time "Phase 3" was finished, there was no one wanting to "buy" anything.

-- Lance Roberts, Real Investment Advice

In each previous case, the market experienced a parabolic advance to the initial peak. A correction ensued, which was dismissed by the mainstream media, and investors alike, as just a "pause that refreshes." They were seemingly proved correct as the markets rebounded shortly thereafter and even set all-time highs. Investors, complacent in the belief that "this time was different" (1999 - a new paradigm, 2007 - Goldilocks economy), continued to hold out hopes the bull market was set to continue.

That was a mistake.

Also, in each period, once the monthly "sell signal" was triggered from a high level, the ensuing correction process took months to complete. This not only reset the market, but valuations as well. In both previous periods, reflexive rallies occurred, which eventually failed. While the 2008 plunge following the Lehman crisis was most similar to the current environment, there was a brief rally following the passage of TARP, which sucked investors in before the additional 22% decline in the first two months of 2009.

Most importantly, the market got very oversold early in both previous bear markets, and stayed that way for the entirety of the bear market. Currently, the market has only just now gotten to a similar oversold condition.

What all the indicators currently suggest is that, while the current correction has been swift and brutal, bear markets are not resolved in a single month.

This is going to take some time.

Bear Market Rally

Over the past couple of weeks, we have been talking about a potential reflexive bounce.

From a purely technical basis, the extreme downside extension, and potential selling exhaustion, has set the markets up for a fairly strong reflexive bounce. This is where fun with math comes in.

As shown in the chart below, after a 35% decline in the markets from the previous highs, a rally to the 38.2% Fibonacci retracement would encompass a 20% advance. Such an advance will "lure" investors back into the market, thinking the "bear market" is over.

This is what "bear market rallies" do and generally inflict the most pain possible on unwitting investors. The reasons for this are many, but primarily investors who were trapped in the recent decline will use the rally to "flee" the markets permanently.

More importantly, as noted above, "bear markets" are not resolved in a single month. Currently, there are too many investors trying to figure out where "the bottom" is, so they can "buy" it.

Bear markets do not end in optimism; they end in despair.

Looking back at 2008, numerous indicators suggest the "bear market" has only just begun. While this does NOT rule out a fairly strong reflexive rally, it suggests that any rally will ultimately fail as the bear market completes its cycle.

This can be seen more clearly in the monthly chart below, which looks at both previous bull and bear markets using a Fibonacci retracement. As shown, from the peak of both previous bull market "bubbles," the market reversed 61.8% of the advance during the "Dot.com" crash, and more than 100% of the advance during the "Financial Crisis."

Given the current bull market cycle was longer, more levered, and more extended than both previous bull markets, a 38.2% decline is unlikely to fulfill the requirements of this reversion. Our ultimate target of 1600-1800 on the S&P 500 remains confirmed by the quarterly chart below.

The current correction process has only just triggered a quarterly sell signal combined with a break from an extreme deviation of the long-term bull-trend back to the 1930s. Both previous bull market peaks coincide with the long-term bull trend at about 1600 on the S&P currently. Given all the stimulus being infused into the markets currently, we broaden our bear market bottom target to 1600-1800, as noted.

The technical signals, which do indeed lag short-term turns in the market, all confirm the "bear market" is only just awakening. While bullish reflexive rallies are very likely, and should be used to your advantage, this is a "traders" market for the time being.

In other words, the new mantra for the market, for the time being, will be to "Sell Rallies" rather than "Buy The Dip."

Yes, the market will rally, and likely substantially so. Just don't forget to take action, make changes, and get on the right side of the trade, before the "bear returns."

Let me conclude by reminding you of Bob Farrell's Rule #8 from our recent newsletter:

Bear markets have three stages - sharp down, reflexive rebound and a drawn-out fundamental downtrend

- Bear markets often START with a sharp and swift decline.

- After this decline, there is an oversold bounce that retraces a portion of that decline.

- The longer-term decline then continues, at a slower and more grinding pace, as the fundamentals deteriorate.

Bear markets often START with a sharp and swift decline.

After this decline, there is an oversold bounce that retraces a portion of that decline.

The longer-term decline then continues, at a slower and more grinding pace, as the fundamentals deteriorate.

Dow Theory also suggests that bear markets consist of three down legs with reflexive rebounds in between.

The chart above shows the stages of the last two primary cyclical bear markets versus today (the 2020 scale has been adjusted to match.)

As would be expected, the "Phase 1" selloff has been brutal.

That selloff sets up a "reflexive bounce." For many individuals, they will "feel like" they are "safe." This is how "bear market rallies" lure investors back in just before they are mauled again in "Phase 3."

Just like in 2000, and 2008, the media/Wall Street will be telling you to just "hold on." Unfortunately, by the time "Phase 3" was finished, there was no one wanting to "buy" anything.

-- Lance Roberts, Real Investment Advice

Saturday, March 21, 2020

the four stages of a bear market

Typically, bear markets have four stages.

Stage one is recognition. Almost everybody shrugs off a bear market’s initial slide as being an ordinary event. The markets rise, and they fall. Treating every bad week as the bear’s arrival would not only shred one’s nerves, but would cause poor performance, should the investor act upon that instinct. Nine times of out 10, realizing a quick 5% or 10% loss would result in a permanent 5% or 10% loss, as stocks quickly return to their previous level.

This market achieved stage one during its third week. Stocks were up slightly for the year, before suddenly dropping 11% in the last week of February. In response, advisory firms issued reassuring notes about how these things happen, and market volatility is natural. The stock market surged the following Monday, failed to hold its gains, and then collapsed in week three—that is, last week. The bear was on.

Stage two is panic. This occurs when shareholders realize that the standard advice failed. Buying on the dip wasn’t easy money, as it is nine times in 10. Rather, it led to greater damage. Along with the pain (and regret) of unexpected losses comes the surprise that the conventional wisdom was wrong. Investors’ faith is tested—and some are found wanting. They sell first, then ask questions later.

We are currently in stage two. It could hardly be otherwise. Along with 1987’s bust, the current stock market crash—it fully deserves that name, with the Dow at the time of this writing being down 34% from its peak—has been the fastest stock-market descent since The Great Depression. It is difficult to apply rational analysis when so much happens, so quickly.

Stage three is stabilization. Stocks halt their decline, thereby ending the impression that they will do nothing but fall. The panic subsides but the situation remains grim. Investors believed during the first stage that stock prices slide on a whim. Now they realize that equities stumbled for good reason, and that until that reason is eliminated, they will continue to struggle. Shareholders’ losses will not soon be recouped.

This period is marked by turbulence. Stocks rally, sometimes furiously, only to be knocked back down. Investor sentiment varies between guarded optimism that the end is at least remotely in sight, and despair that the hope was false. This is typically the bear market’s longest period, extending for several months. (Several years for The Great Depression, but we do not wish to emulate that example.)

Stage four is anticipation. This is when stocks start their recovery. As with the bear market’s beginning, almost nobody recognizes its end until after the fact. The news at the time tends to be almost unrelievedly grim, accompanied by articles about how stocks’ golden days have passed. However, some investors perceive economic improvement distantly in the future. They make their bids, and stocks begin to rise.

A classic case occurred in March 2009. The recession was in its terrifying midst. Real U.S. gross domestic product declined that quarter, and the next quarter, and the quarter after that. The Morningstar Ibbotson Conference was held that month to empty seats, with the keynote speaker predicting several more months of equity losses. The rally began the next day.

Example #1: Black Monday

This is how the four stages played out 33 years ago:

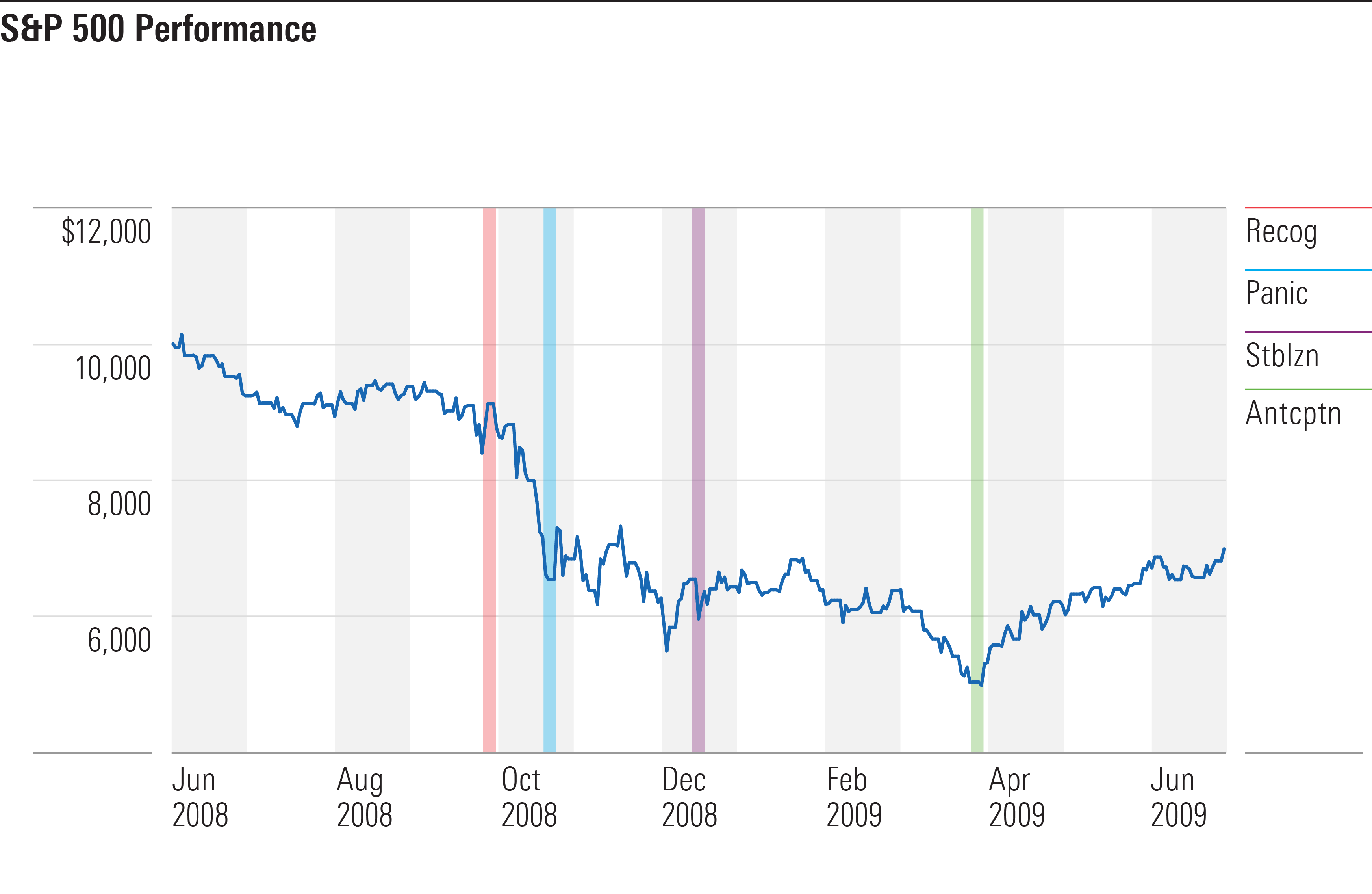

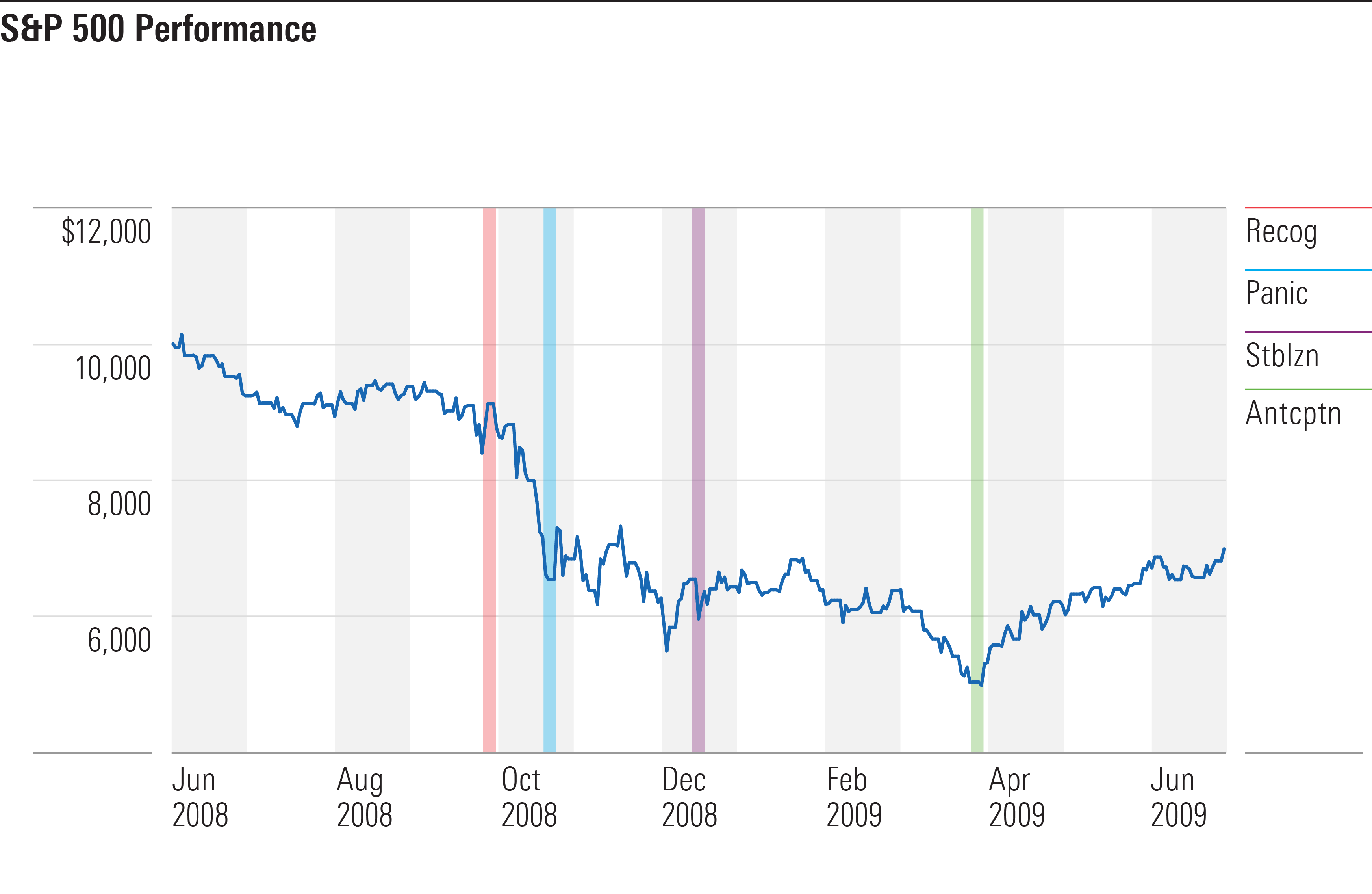

Example #2: Financial Crisis

And this is how they operated more recently, from late 2008 through early 2009:

This scheme applies to bear markets that are primarily caused by recession fears. In addition to the two historic bears charted above, the scheme can be used to map the much smaller slump of 1990, and 1981’s decline, and 1970’s sell-off. Of course, the details for each of those markets vary, sometimes substantially—it would be reductive to imply otherwise—but the pattern is roughly similar.

However, the blueprint does not work for bear markets that arise from other causes. For example, the stock market’s grinding decline from 1973 through 1974 doesn’t map well to the four stages, because it was caused by steadily increasing inflation fears. The 2000-02 technology-stock implosion also fails the test, because the major concern as the New Era concluded was that equity prices had risen too high, not—aside from some of the Internet stocks—that earnings would disappear.

The question then becomes, does the current bear market fall into the first category or the second?

The former would be greatly preferable. With that scenario, the enormous uncertainty about the spread of the coronavirus, and the economic damage that the containment efforts will wreak, disappears over the next few months. The problems will remain large and numbers, but they will at least be known quantities—and the financial markets are adept at planning for what is known.

Should the picture become clearer, the four-stage scheme figures to be relevant. Fairly soon, I should think, stocks will enter the third stage, that of stabilization. That doesn’t mean that they won’t decline further, but the struggle will at least be bounded. Within months, not years, the stock market recovery should begin.

On the other hand, should uncertainties remain high and unresolved, perhaps because the virus’s behavior confounds the scientists, or because the financial stimulus efforts prove ineffective, then all bets are off. I do not know how to analyze such a situation. I hope that I never shall.

-- John Rekenthaler, Morningstar

Stage one is recognition. Almost everybody shrugs off a bear market’s initial slide as being an ordinary event. The markets rise, and they fall. Treating every bad week as the bear’s arrival would not only shred one’s nerves, but would cause poor performance, should the investor act upon that instinct. Nine times of out 10, realizing a quick 5% or 10% loss would result in a permanent 5% or 10% loss, as stocks quickly return to their previous level.

This market achieved stage one during its third week. Stocks were up slightly for the year, before suddenly dropping 11% in the last week of February. In response, advisory firms issued reassuring notes about how these things happen, and market volatility is natural. The stock market surged the following Monday, failed to hold its gains, and then collapsed in week three—that is, last week. The bear was on.

Stage two is panic. This occurs when shareholders realize that the standard advice failed. Buying on the dip wasn’t easy money, as it is nine times in 10. Rather, it led to greater damage. Along with the pain (and regret) of unexpected losses comes the surprise that the conventional wisdom was wrong. Investors’ faith is tested—and some are found wanting. They sell first, then ask questions later.

We are currently in stage two. It could hardly be otherwise. Along with 1987’s bust, the current stock market crash—it fully deserves that name, with the Dow at the time of this writing being down 34% from its peak—has been the fastest stock-market descent since The Great Depression. It is difficult to apply rational analysis when so much happens, so quickly.

Stage three is stabilization. Stocks halt their decline, thereby ending the impression that they will do nothing but fall. The panic subsides but the situation remains grim. Investors believed during the first stage that stock prices slide on a whim. Now they realize that equities stumbled for good reason, and that until that reason is eliminated, they will continue to struggle. Shareholders’ losses will not soon be recouped.

This period is marked by turbulence. Stocks rally, sometimes furiously, only to be knocked back down. Investor sentiment varies between guarded optimism that the end is at least remotely in sight, and despair that the hope was false. This is typically the bear market’s longest period, extending for several months. (Several years for The Great Depression, but we do not wish to emulate that example.)

Stage four is anticipation. This is when stocks start their recovery. As with the bear market’s beginning, almost nobody recognizes its end until after the fact. The news at the time tends to be almost unrelievedly grim, accompanied by articles about how stocks’ golden days have passed. However, some investors perceive economic improvement distantly in the future. They make their bids, and stocks begin to rise.

A classic case occurred in March 2009. The recession was in its terrifying midst. Real U.S. gross domestic product declined that quarter, and the next quarter, and the quarter after that. The Morningstar Ibbotson Conference was held that month to empty seats, with the keynote speaker predicting several more months of equity losses. The rally began the next day.

Example #1: Black Monday

This is how the four stages played out 33 years ago:

Example #2: Financial Crisis

And this is how they operated more recently, from late 2008 through early 2009:

This scheme applies to bear markets that are primarily caused by recession fears. In addition to the two historic bears charted above, the scheme can be used to map the much smaller slump of 1990, and 1981’s decline, and 1970’s sell-off. Of course, the details for each of those markets vary, sometimes substantially—it would be reductive to imply otherwise—but the pattern is roughly similar.

However, the blueprint does not work for bear markets that arise from other causes. For example, the stock market’s grinding decline from 1973 through 1974 doesn’t map well to the four stages, because it was caused by steadily increasing inflation fears. The 2000-02 technology-stock implosion also fails the test, because the major concern as the New Era concluded was that equity prices had risen too high, not—aside from some of the Internet stocks—that earnings would disappear.

The question then becomes, does the current bear market fall into the first category or the second?

The former would be greatly preferable. With that scenario, the enormous uncertainty about the spread of the coronavirus, and the economic damage that the containment efforts will wreak, disappears over the next few months. The problems will remain large and numbers, but they will at least be known quantities—and the financial markets are adept at planning for what is known.

Should the picture become clearer, the four-stage scheme figures to be relevant. Fairly soon, I should think, stocks will enter the third stage, that of stabilization. That doesn’t mean that they won’t decline further, but the struggle will at least be bounded. Within months, not years, the stock market recovery should begin.

On the other hand, should uncertainties remain high and unresolved, perhaps because the virus’s behavior confounds the scientists, or because the financial stimulus efforts prove ineffective, then all bets are off. I do not know how to analyze such a situation. I hope that I never shall.

-- John Rekenthaler, Morningstar

crises and the stock market

Comparing the Current Pandemic to the Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918 and 1919

World War I was raging when the Spanish flu pandemic arrived, infecting some 500 million people worldwide (27% of the population) and killing roughly 40 million people, including 675,000 in the US alone.

There are a lot of takeaways from the Spanish flu pandemic’s effect on the world, but the stock market’s response may be the most surprising. If you look at the Dow Jones Industrial Average during the apex of the outbreaks (there were a few waves) in 1918 and 1919, you find that the index rose by just under 17% with dividends reinvested. Economic production from the war no doubt boosted activity during that time, and euphoria when the war ended in 1918 likely also contributed.

In all, this history lesson should serve as a stark reminder that the world can endure a world war and a lethal pandemic and still fight and grow through it. When the final wave of the Spanish flu subsided in February 1919, the market surged some 50% through November of that year. When a fear fades, stocks can surge.

This is a Good Reminder of How the Stock Market Works

In times like these, it’s also important for investors to take a step back and remember how the stock market works. Investors get long stretches of gains when the market trends higher (approximately +400% in this most recent bull run), and then from time to time, we experience clusters of scary downside volatility and bear markets when 20+% is quickly wiped out. But then when the crisis fades and fears abate, the next twelve months consistently delivers a strong comeback:

Long-term investors – and hopefully the folks who read my columns regularly – know that during a panic, an investor should look to snap up bargains as almost everyone runs for the exits. It’s the strategy of being “greedy when others are fearful,” as Warren Buffet put it. It sounds easy in theory, but it is very difficult in practice. In my view, now is a good time to buy stocks – it’s a better time than almost any other time since the ’08 crisis – it’s just psychologically almost impossible to implement. The history of the US economic system is a history of the triumph of the optimists. I believe the panic we see today will recede and money will transfer from those who panic to those who have a steady hand.

The issue is that there is no way to know when the market will stage its strong recovery, though history does tell us that it usually happens in close proximity to the scariest down days (much like the +9% surge we saw last Friday).6 Here’s a key stat to remember: over the last 20 years, 24 of the 25 worst trading days were within one month of the 25 best trading days.7 This speaks to the perils of trying to time exit and entry points during heightened volatility like we’re seeing right now. Doing so means potentially – if not probably – missing out on the market’s best rallies that every equity investor needs to drive long-term investing success.

-- Mitch on the Markets, 3/19/20

* * *

The top 10 worst bear markets (using the Dow), following the Great Depression, shows that it declines on average by -39.27%. And it lasts on average of 16.9 months. [The market dropped 89.2% from top to bottom during the Great Depression.]

The biggest bear market in that study was the last one (10/2007-3/2009) during the housing/financial crisis. It was dubbed the Great Recession and the market plunged by -54.43%. But it’s worth noting that our economy and financial system back then were on pretty shaky ground. A starkly different situation than how we entered this one.

This bear market, at its worst, saw the Dow down by -35.98%, the S&P down by -32.29%, and the Nasdaq down by -31.67%.

Not that far from the average. Although, a ways to go to the worst case study.

But the rallies that followed have been even bigger. Within a year after a bear market, stocks surge on average of 44.74%. And go on to gain on average 66.34% by year 3.

Following the Great Recession, the market gained 63.40% in year 1; 100.58% by year 3; 153.58% by year 5; and more than 357% during the entire 11+ year bull market.

And given the strength of the economy going into this, it’s all the more likely that we’ll bounce back big and in record time.

Trading The Bear

Just like stocks need to fall by -20% for a bull market to end and a bear market to begin, they also need to go up by 20% for a bear market to end and a bull market to begin.

For the Dow, it needs to close at or above 23,008.78 for a new bull market to begin.

For the S&P, it’s 2,765.90.

And for the Nasdaq, it’s 8,255.42.

Set yourself an alert. When we close above those levels, the bear market will officially be over and a new bull market will have begun.

But that doesn’t mean you have to wait to start nibbling at your favorite stocks and their discount bargain prices.

Some may go lower. And some may not. But they are likely much lower now than where they were just a few short weeks ago. And much closer to the bottom (if they haven’t already hit it).

Riding The Bull

The big gains that follow a bear market can be quite spectacular.

But since a large part of any bull market recovery typically comes at the very beginning, it’s imperative that you stay in the market.

The trick is to get into the right stocks.

There’s nothing wrong with raising cash by getting out of your laggards and poorest performers – stocks you know you should have gotten out of long before this pullback even happened. Or getting rid of those stocks that will have an uphill battle recovering even when this is over.

But then make sure to replace them with the strongest stocks that will be the new market leaders.

The point is, you want to be building your dream portfolio now, near the bottom.

And by the time the new bull market is underway, you’ll be all in with the strongest stocks, and beating the market.

-- Kevin Matras, Weekend Wisdom, 3/20/20

* * *

Like last week, this week was another one for the history books. The SPX continued the triple-digit see-saw action that began last week and through Wednesday (3/18) had moved more than 4% (up or down) for 8 consecutive sessions. According to my calculations that has never happened before. However, the down days have been larger than the up days and as a result the SPX remains solidly in bear market territory. While the SPX did test the December 2018 correction low of 2,351 four times, it ultimately held (which is encouraging) so that support level remains.

Since the SPX remains in bear market territory, here is where this new bear market stands relative to other bear markets in history. As you can see, despite being only 29 days old, with a decline of 28.8% through Thursday (3/19) it has already surpassed 5 other bear markets in magnitude.

Outlook:

While the virus outbreak seems to be accelerating outside of China, numerous monetary and fiscal initiatives have been announced to keep businesses solvent and employees paid. And while there are finally some indications of bargain hunting, two consecutive up days have not occurred since mid-February. Caution and patience is still advised.

-- Randy Frederick, Weekly Trader's Outlook, 3/20/20

World War I was raging when the Spanish flu pandemic arrived, infecting some 500 million people worldwide (27% of the population) and killing roughly 40 million people, including 675,000 in the US alone.

There are a lot of takeaways from the Spanish flu pandemic’s effect on the world, but the stock market’s response may be the most surprising. If you look at the Dow Jones Industrial Average during the apex of the outbreaks (there were a few waves) in 1918 and 1919, you find that the index rose by just under 17% with dividends reinvested. Economic production from the war no doubt boosted activity during that time, and euphoria when the war ended in 1918 likely also contributed.

In all, this history lesson should serve as a stark reminder that the world can endure a world war and a lethal pandemic and still fight and grow through it. When the final wave of the Spanish flu subsided in February 1919, the market surged some 50% through November of that year. When a fear fades, stocks can surge.

This is a Good Reminder of How the Stock Market Works

In times like these, it’s also important for investors to take a step back and remember how the stock market works. Investors get long stretches of gains when the market trends higher (approximately +400% in this most recent bull run), and then from time to time, we experience clusters of scary downside volatility and bear markets when 20+% is quickly wiped out. But then when the crisis fades and fears abate, the next twelve months consistently delivers a strong comeback: